Alessia Lai 1, Annalisa Bergna 1, Carla Della Ventura 1, Maciej Tarkowski 1, Agostino Riva 1,2, Davide Moschese 3, Giuliano Rizzardini 3, Spinello Antinori 1,2, Gianguglielmo Zehender 1

1 Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan

2 III Division of Infectious Diseases, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Luigi Sacco Hospital, Milan, Italy

3 Department of Infectious Diseases, Luigi Sacco Hospital, Milan, Italy

Monkeypox is a zoonotic emerging disease caused by the Monkeypox virus (MPXV), which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus in the Poxviridae family (1). The disease has been classically described to be similar to smallpox with skin lesions appearing on the third day and evolving with a synchronous pattern. Lymphadenopathy has been considered an important distinguishing feature with smallpox.

The virus is transmitted from one person to another by close contact with lesions, body fluids, respiratory droplets and contaminated materials. The Monkeypox lethality rate ranges from 1 to 10% (2), with highest proportion in children. MPXV forms two distinct clades: the MPXV Congo Basin clade viruses that are endemic in the Congo Basin and the MPXV West African clade viruses that have been isolated in West Africa and appear to cause a less severe, and less interhuman transmissible disease (3).

Although MPXV is mostly linked to Africa travel, several cases have been recently detected around the world with increasing frequency (United Kingdom, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Italy, Canada, Belgium, Australia, France, Germany, and the USA). According to WHO data (https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON385), as of 21 May, 92 confirmed and 28 suspect cases of Monkeypox have been reported.

Based on currently available information, cases have mainly but not exclusively been identified amongst men who have sex with men (MSM). Most of the confirmed reported cases present lesions in the perianal and perigenital area with few skin lesions with an asynchronous pattern of evolution. As the extent of local transmission is unclear at this stage, there is a high urgency of further investigation.

Here we report the full genome of an Italian case obtained from a swab collected on May 25th from skin lesions of a male patient.

On May 24 a 33-yr old man presented to our ward with a perianal ulcer, inguinal bilateral adenopathy and few scattered papular and vesicular skin lesions localized on both elbows, back, buttock and left foot. He lived in Lisbon (Portugal) and arrived in Italy on May 18th. A few days before the appearance of skin lesions he complained of fever (38.5°C) of one-day duration associated with pharyngodynia and sneezing.

Brief description of the methods

DNA was extracted from all samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), fragmented using a Covaris M220 ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) and checked using a 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies, USA). The libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequencing was performed using a Miseq sequencer (Illumina) with 300 cycles.

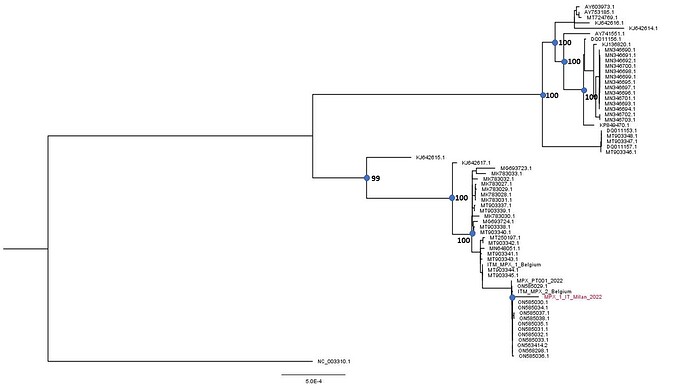

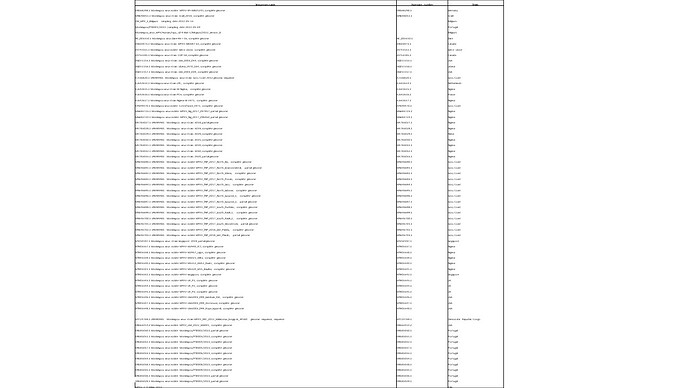

Reads were mapped to a reference genome sequences (MT903343.1) using Geneious software V.11 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) (http://www.geneious.com) obtaining an average depth of 19x. The patient’s viral genome was aligned with 66 reference genomes obtained from public databases (Table 1) using MAFFT (4) and manually cropped using BioEdit v. 7.2.6.1 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html).

Mean difference between sequences collected in 2018-2019 period and the current outbreak was 100.66 nucleotides, while within 2022 whole genomes differences were 6 nucleotides.

Preliminary phylogenetic analysis was performed by Maximum likelihood using Iqtree software under a K3PU+F+I model selected by ModelFinder (http://www.iqtree.org/on). The tree shows that the obtained genome belongs to the West African clade of MPXV and is most closely related to the recently uploaded genome from the outbreak in Portugal providing further evidence of substantial community spread in Europe.

The Italian sequence is depicted in red. The sequence has been submitted to GenBank (accession number: ON622721) .

References

- Di Giulio DB, Eckburg PB. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004 Jan;4(1):15-25. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00856-9. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2004 Apr;4(4):251. PMID: 14720564.

- Durski KN, McCollum AM, Nakazawa Y, Petersen BW, Reynolds MG, Briand S, Djingarey MH, Olson V, Damon IK, Khalakdina A. Emergence of Monkeypox - West and Central Africa, 1970-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Mar 16;67(10):306-310. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a5. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Apr 27;67(16):479. PMID: 29543790; PMCID: PMC5857192.

- Hutson CL, Lee KN, Abel J, Carroll DS, Montgomery JM, Olson VA, Li Y, Davidson W, Hughes C, Dillon M, Spurlock P, Kazmierczak JJ, Austin C, Miser L, Sorhage FE, Howell J, Davis JP, Reynolds MG, Braden Z, Karem KL, Damon IK, Regnery RL. Monkeypox zoonotic associations: insights from laboratory evaluation of animals associated with the multi-state US outbreak. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Apr;76(4):757-68. PMID: 17426184.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013 Apr;30(4):772-80. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. Epub 2013 Jan 16. PMID: 23329690; PMCID: PMC3603318.